The traditional food of Venice is a weird, stratified blend of thriftiness and opulence, of local and far away ingredients.

Exploring it comes as an irreverent challenge to those who preach the gospel of purity and culinary authenticity. Because here, everything is mixed up, including our own identity. Originally, there was no pizza, no lasagne. Instead, an array of imported spices and cargoes of sugar. Almonds and raisins. Seafood and mutton. Cabbage and rice. Soft polenta.

When Marco and Sabrina, the authors of

, asked me to connect Venice to one of their many travel and culinary experiences, I knew it would be a fascinating quest. And when they mentioned a cruise down the Nile, it just hit me. Egypt, that’s where I’ll look.For centuries, Egypt was Venice's preferred gateway to the goods coming from the East. It must have seen tremendous flows of people, products, and, of course, foods. How intriguing to think that our local dishes might have evolved from the habits and tastes of other cultures. But what dish? Which preparation?

I wasn't quite prepared to learn that the very emblem of Venetian identity - our beloved carnival fritters, the official national sweet of the Venetian Republic - is, in fact, the fruit of a faraway country (more than one, actually!).

Carnival fritters are deep-fried full moons of spongy yeasted dough enriched with raisins, pine nuts, and citrus notes. They are the most revered treat by all Venetians, first touching land in Venice after a sea trip from Egypt.

The Most Beloved Carnival Treat

It’s fitting to bring you this post as Carnival reaches its peak in these very days. If you’ve ever been in Venice at this time of the year, I’m sure you didn’t fail to notice (and savour) the hundreds of round, sugared, globes piled up in front of the windows of every bakery in town.

Carnival fritters, in their “classic” version, are deep-fried doughnuts made of yeasted dough enriched with raisins, pine nuts, and citrus zest. Frittelle (fritoa in Venetian dialect) is the typical treat of the Venice carnival and, with some variations, of the whole Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia regions and Istria. They are sold in bakeries and supermarkets all throughout January and February and what a joy they bring.

Historically, frittelle were prepared and sold on the street on huge plates on tripods between December 26 until the end of the carnival celebrations, making them a proper street food. Only a small number of men could make and sell them, a corporation no one could join unless they had a father who was a "fritolero" himself.

Thanks to the brilliant work of writers and scholars throughout history - and in perfect circularity - we now know that the ancestors of Venetian frittelle were around at least since the Roman times. They migrated to the Middle East through the Eastern Roman Empire, mutating in the process, planting roots in the heart of Persia and then Egypt from where they headed back to the Italian peninsula, reaching Venice thanks to the commercial relation that tied the two territories. They were called Zalabiyeh in Arabic and became fritoe in Venice (frittelle in Italian).

Pedigreed vs Commoner Fritters

Below I’m sharing the recipe that emerged from a week of testing. It yields a scrumptious fritter that tastes just right.

This recipe is also the half-blood offspring of a recipe from the private archives of a noble Venetian family, from which I borrow the decadent ingredient list, and an anonymous recipe recorded from the oral tradition, from which I adopt the thrifty method.

If you’re new to this newsletter, you may not know that I’m slowly testing and translating an old book of traditional Venetian cuisine.1

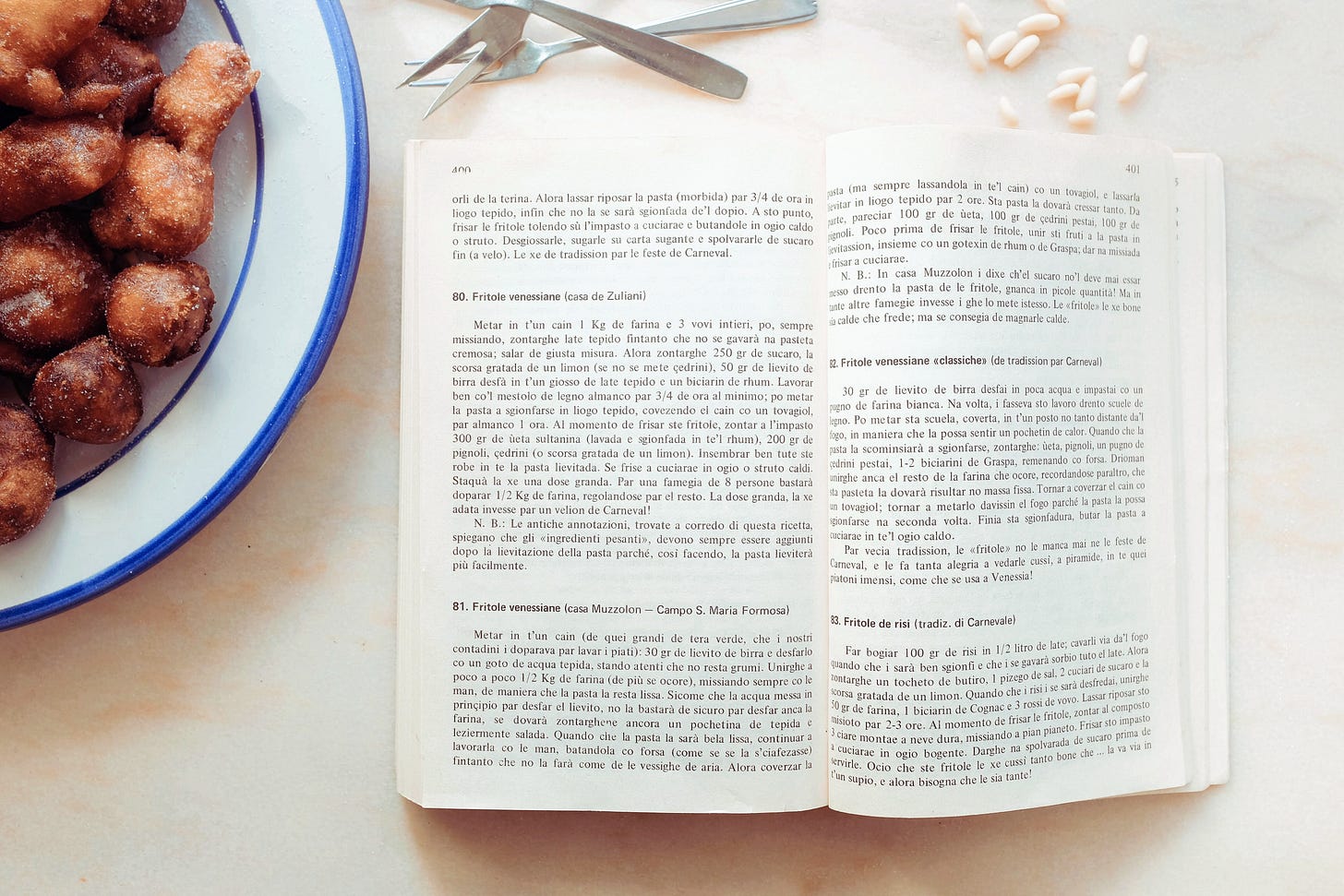

The book, entirely written in the local dialect, lists almost 1000 recipes, with 4 recipes devoted to classic frittelle. Three of them come from the archives of local patrician families,2 while the fourth one doesn’t list a source, so I assume it comes from the shared local oral tradition.

All four recipes are similar but different at the same time - which made testing them an aven more stimulating challenge as I know how much of a difference small changes can make to the outcome of a recipe.

It turns out that there are two main methods to prepare the batter for these fritters: the first and most common method requires anything from 45 to 60 minutes of energetic mixing by hand (or using a kitchen robot which I do not own). The three recipes of patrician origins all feature this method.

The second method, instead, ditches the mixing and opts for a double raising instead. No strenous physical activity needed (nor expensive equipment). The anonymous recipe relies on this expedient to obtain a bubbly, gluey batter. An old friend of mine who is a trained chef uses this very method.

At first, I was only interested in the three "pedigreed" recipes, but the anonymous one proved to be a game changer, simplifying the whole process tremendously.

Venice, like many other places, had a stratified society made of workers, artisans, merchants and very powerful families with enormous riches, palaces, countryside villas… and servers. Obviously, commoners could not rely on private chefs and helpers. So it only makes sense that they’d find smart workarounds to simplify heavy tasks.

The 5 Pillars of Classic Venetian Fritters

Regardless of the minor differences in how each family, bakery, and restaurant make their fritters, there are five unmovable pillars that define a classic Venetian frittella:

a batter leavened with brewer's yeast

citrus notes, raisins (and most times pine nuts), a drop of booze

a soft, spongy texture

a globular shape, and a burnished color

a smothering of granulated sugar

Important! To make the the other most common version of Venetian fritters (cream-filled), you will need a an entirely different batter!3

RECIPE: Classic Venetian Carnival Fritters

Adapted from A Tola Co I Nostri Veci La Cucina Veneziana by Mariù Salvatori De Zuliani

These fritters are very straighforward to make. The only thing you need is enough time to let the batter rise twice (around 1.5 hour in total) and the time required for frying (40 min max including heating the oil).

A food thermometer will give you the self-confidence to master the frying station (it did for me!) and avoid smoking up the house. La Cucina Italiana, one of the most respected cookery magazines in Italy and the only one with a test kitchen, suggests leaving three almonds with their skin on in the frying oil from start to finish to reduce the smell of deep frying. It works! Now you have no more excuses not to start frying :)

US measurements in the footnotes.4

Yields 5 portions.

Ingredients

Brewer’s yeast, 13gr

Water, 50ml, warm

Flour, 250gr, all purpose

Sugar, 150gr, caster

Raisins, 70gr

Rum/Grappa, 50ml

Pine nuts, 70gr

Lemon, 1, organic

Orange, 1, organic

Egg, 1, medium

Milk, 150ml, warm

Peanut oil, 2Lt

Almonds, 3, with skin on (optional)

Utensils

A pan suitable for deep frying (I use a wok)

Food thermometer (optional, but useful) or a wooden spoon

Kitchen paper towels

Spider strainer or similar

2 spoons

Large bowl

Method

Step 1: In a large mixing bowl, combine the brewer's yeast with the warm water. Use your fingers to dissolve the yeast. Incorporate 25gr flour and 15gr sugar. Let the mixture rest, covered in a warm place, for 30 minutes, until it’s doubled in volume.

Step 2: Meanwhile, soak the raisins in the dark rum, lightly toast the pine nuts until they're fragrant, and zest 1 lemon and 1 orange. Set aside.

Step 3: When the mixture has leavened and is nice and foamy, warm up the milk and set aside. Then add the raisins, pine nuts, citrus zests, beaten egg and 50 gr of sugar. Mix gently, then add the warm milk and mix again. Finally, slowly incorporate the remaining flour.

Step 4: Cover with a cloth and let rise in a warm place for 1 hour. After 1 hour, the batter should have a nicely risen, bubbly and gluey texture. Don't even think to mix it. You'll spoon it as it is into the hot oil.

Step 5: Heat the oil in a deep-frying pan with 3 almonds with their skin on. Once the oil reaches 160°C-170°C (320°F - 340°F)5 begin dropping 3/4 spoonfuls6 of batter into the pan as quickly as you can. Fry the fritters in batches (approximately three batches in total). You can experiment with the size of the fritters, but you'll have to adapt the cooking time. Fry the dough balls until golden brown, using a slotted spoon to flip them around to help with the cooking.

Step 6: Remove the frittelle from the oil and place them onto a dish covered with paper towels to drain. Sprinkle with granulated sugar and serve warm. They should be pillowy soft and moist.

These fritters can be kept for up to 2 days in an airtight container lined with paper towels. Note that they will dry out quite quickly over time.

About Me

My name is Sinù Fogarizzu and I’m a vegetarian food writer from the mainland of Venice, Italy. In 2021, I launched Dash of Prosecco, a Substack newsletter about learning to cook, identity and Venetian cuisine. I’m on Instagram & Twitter.

A Tola Co I Nostri Veci by Mariù Salvatori de Zuliani (1971) - This amazing book is the result of a gigantic research work by hand of an elusive woman, a descendant of the de Zuliani family - a patrician family boasting very deep roots. Thanks to the genius of Mariù, the author, and her fleet of (mostly female) collaborators nearly 1,000 recipes of traditional dishes from Venice, its mainland and historical territories are preserved on the pages of what is now considered the “Bible” of Venetian cuisine. Modern Venetians respect it deeply.

These are the three patrician Venetian families that had contributed the recipes I tested for this newsletter: Gaggia, de Zuliani and Muzzolon.

Pick your batter. The classic Venetian frittella is leavened with brewer's yeast and has a solid crumb. To make cream-filled frittelle (custard, chantilly, sabayon), you need to use a different batter, similar to pate à choux, which produces hollow and light frittelle. Unlike the classic method, this batter doesn't require yeast. You cook the flour with milk, use a high number of eggs, and obtain a solid mixture, not liquid or almost liquid like the classic frittella batter. Check out this post by

for some inspiration.

Ingredients in US measurements: 1 packet (2 1/4 tsp) active dry yeast (or 13g brewer's yeast); 1/4 cup warm water; 1 3/4 cups all purpose flour; 3/4 cup caster sugar; 1/2 cup raisins; 3 1/2 tbsp dark rum (or grappa); 1/2 cup pine nuts; Zest of 1 organic lemon; Zest of 1 organic orange; 1 medium egg; 2/3 cup warm milk; 8 1/2 cups peanut oil (2L); 3 almonds with skin on (optional).

Oil temperature: If you’re not familiar with deep frying and don’t have a food thermometer try the wooden spoon test: insert the end tip of a wooden spoon into the hot oil and drag it around. If bubbles engulf it, forming a tail as you move it, then the oil has reached the right temperature.

This Instagram post shows exactly how to portion the batter into hot oil. Their batter is thinner than the one I share in this post but firmer compared to others I've seen around. Each family, bakery and restaurant have their own version.

Share this post